A substantial centennial will be celebrated the day before Election Day and, locally, it’s a story whose colorful cast of characters includes several with Keuka College connections.

Nov. 6 marks the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in New York.

While the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote nationwide in 1920, full suffrage had already been achieved in nearly a third of the states. Indeed, New York was the 14th state to expand voting rights – although the first east of the Mississippi. As such, it is credited by many historians with adding momentum to the national suffragist movement.

But the victory was not easily won.

Among the hurdles were good old-fashioned chauvinism, of course, but also an early 20th-century version of fake news: the persistent claim that women did not want the vote.

So proponents took to the streets – not to agitate but to aggregate.

“To answer charges by opponents that most women did not want to vote,” writes history professor, author and blogger Susan Ingalls Lewis, “suffragists spent more than a year going door-to-door in nearly every city and town in the state, collecting the signatures of over one million women who said that they wanted to vote.”

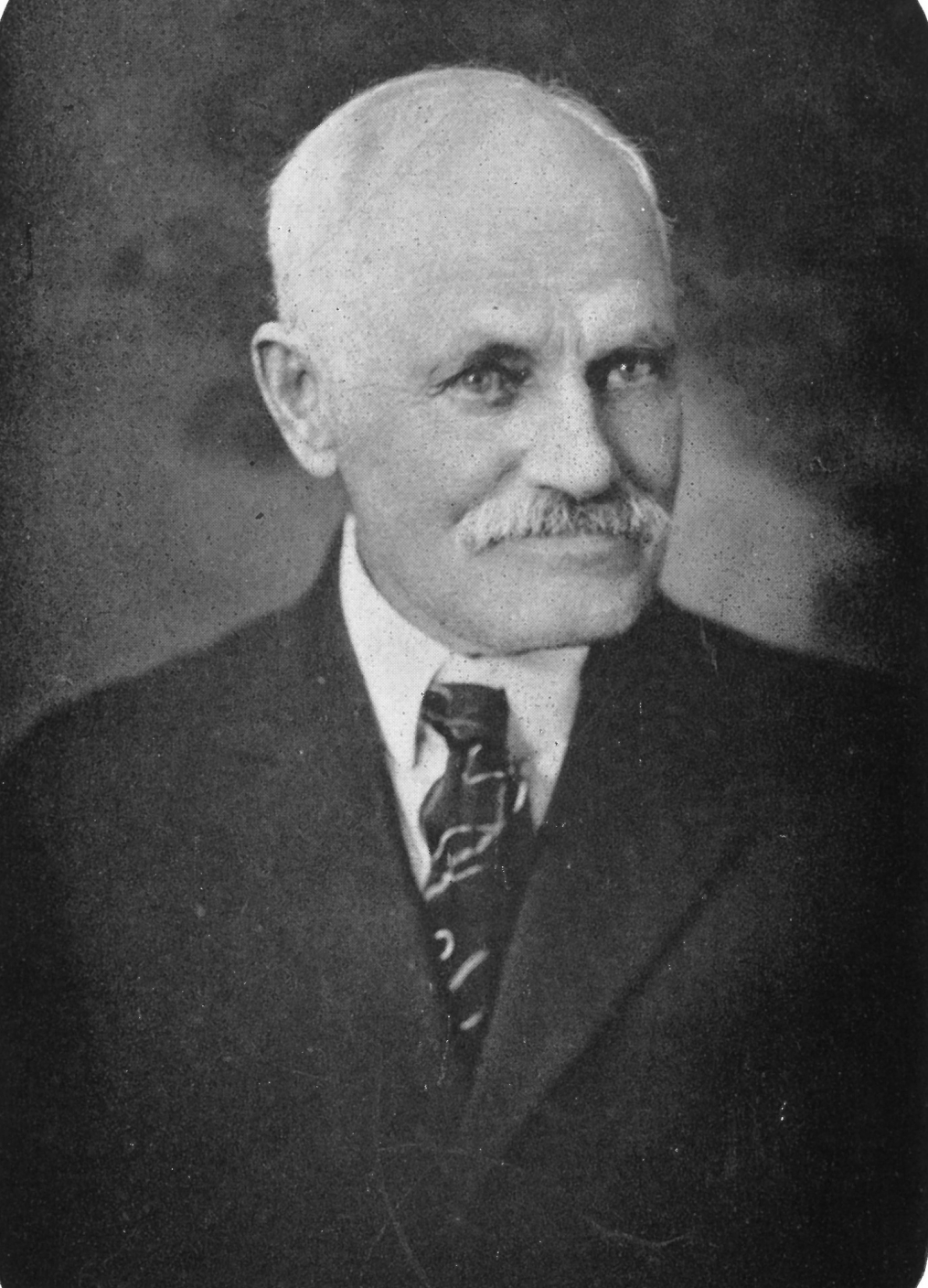

Enter Keuka College Trustee and Treasurer Zebina Flavius (Z.F.) Griffin, his wife, Elizabeth (Libby) Cilley Griffin, and their daughter, Frankie Lawrence Griffin Merson.

On a mission

As devout Baptist missionaries, the family did not cringe from seeking out converts. Z.F. was a minister, after all, and Libby made a solo trip to India while still a young woman to engage in missionary work.

Their mission in 1916: Win women the right to vote.

The Griffins were among those most active in Yates County in canvassing for the cause – and for the signatures from women affirming their desire to obtain the vote – according to Lisa M. Harper, administrative assistant and educator with the Yates County History Center.

“(Z.F.) believed in the women’s right to vote and was delighted to get into an active campaign leading to victory,” says Harper.

That meant hitting the road.

“He would occasionally borrow a car,” says Harper, “to take women around to many of the small villages in the county to speak about the importance of suffrage.”

Not that everyone was interested in listening.

“Z.F. was preaching about suffrage on the corner of Main Street in Penn Yan – about where Pinckney’s (hardware store) is now,” recounts Harper. “He was going on and on, as a preacher would, and his friends would see him, and they would cross the street, then cross the other street, and go around him so they didn’t have to engage with him or listen to his speech.”

Gathering signatures

Pedestrians may have been able to avoid Z.F., but Libby Griffin didn’t seem to let them get away so easily.

The chairwoman of the Yates County Suffrage Party led the charge to collect women’s names on their vote-backing petitions. Of the roughly 3,100 signatures eventually collected, Libby accounted for some 600 of them.

Eventually, more than 1 million signatures were amassed statewide, attached to placards, and paraded through the streets of Manhattan in a pre-Election Day show of strength.

Daughter Frankie, a 1904 Keuka College graduate who also taught at and later led the Political Science & Sociology Department at the College, was just as vocal a supporter. Literally.

Harper reports Frankie became an organizer and demonstration leader for the state Women’s Suffrage Party, and was a much sought-after speaker on women’s issues.

While Frankie may have been overshadowed in the national consciousness by better-known suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Susan B. Anthony, she has not been forgotten locally. The Penn Yan Public Library’s annual meeting in March featured a talk by Merril Race, portraying Frankie, as part of a presentation called “Celebrating Suffrage!”

On to victory

Did the Griffins’ work pay off? Let’s just say they won the war but lost the battle.

The suffrage measure passed by more than 100,000 votes statewide but, then as now, the margin of victory came courtesy of New York City. The vote carried in Buffalo and Syracuse but was defeated in Albany and Rochester (Susan B. Anthony’s hometown, no less!).

And in Yates County, 2,242 no’s overwhelmed 1,425 yesses. That’s not entirely surprising, says Harper.

“Yates County was, and is traditionally a conservative and Republican county,” she says “FDR could not carry Yates County in all four of his tries.”

None of which diminishes the efforts of Z.F., Libby, Frankie, and the hundreds of other suffragists and supporters who finally secured full voting rights for women in New York – 69 years after the first Women’s Rights Convention in nearby Seneca Falls, 39 years after the Nineteenth Amendment was introduced in Congress, and, disappointingly, 15 and 11 years respectively after the deaths of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

The anniversary of that achievement is being celebrated, among other places, at the Yates County History Center’s L. Caroline Underwood Museum on Chapel Street in Penn Yan, where placards containing the original signatures collected some 100 years ago by Libby Griffin and other local suffrage proponents are among the items exhibited.

The “Hear Our One Voice: Women’s Suffrage Exhibit” will be on display at least through the end of the year, says Harper.

The story of Yates County’s role in the state suffrage movement is an early example of how the College and the Community – through events big and small, benign and historic – have been shaping each other’s history, and futures, for more than 100 years.